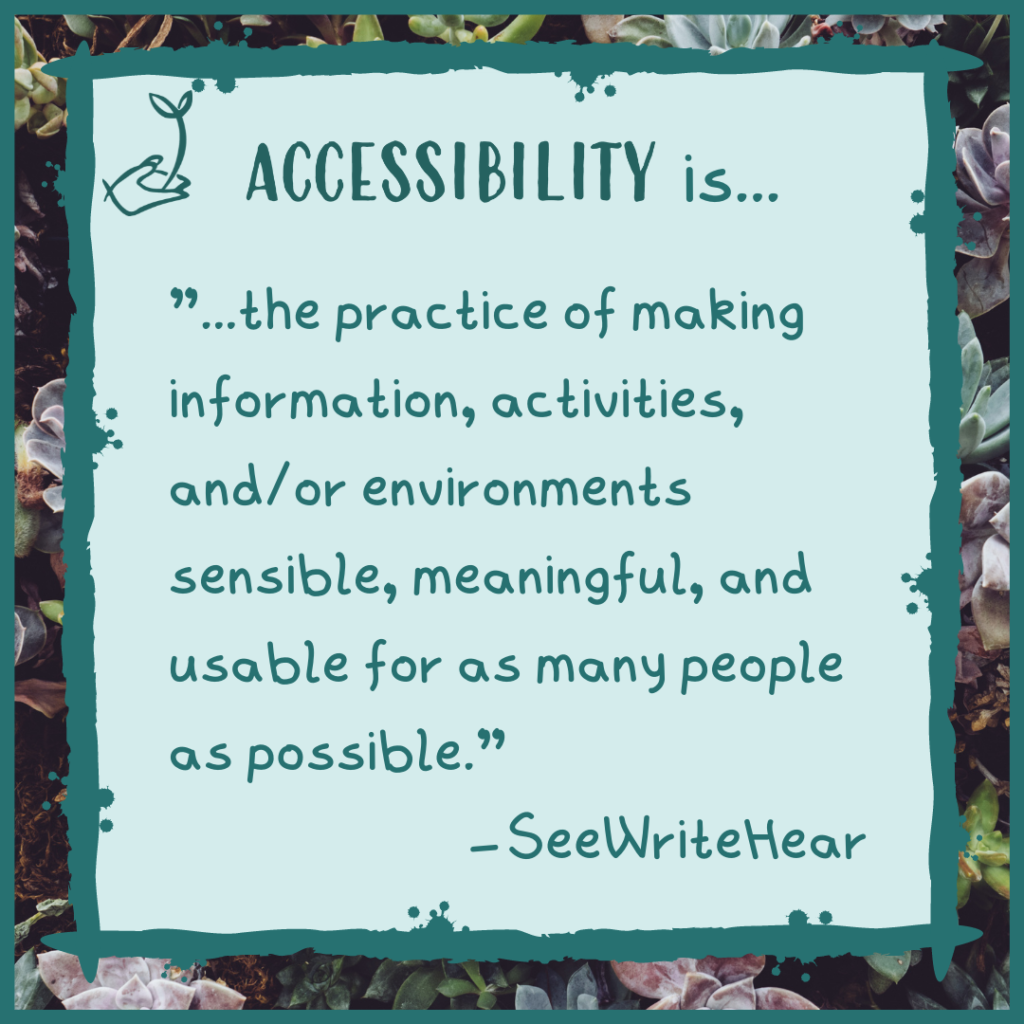

So, when we call ourselves Accessibility in Therapy, what do we mean by this? We picked this word specifically, rather than other words that might be more popular in the field at the moment, because it best reflects exactly what we are working towards.

What is Accessibility?

We looked at how others define Accessibility, and our favourite definition is this one by the US company SeeWriteHear. What we like about this definition is…

- It doesn’t just focus on physical access of spaces an environments – it acknowledges that it’s important to consider information (things like your website, resources you write, and your language) and activities (your service, the way you work, your contracting).

- It doesn’t just look at whether someone is technically able to use something. If a therapy practice isn’t sensible, it can be harmful or re-traumatising. If it isn’t meaningful to them and their world, then there won’t be much of a chance for growth and healing.

- It acknowledges that you cannot expect to be fully accessible to all people all of the time – working to meet the needs of as many people as possible is a constant piece of work.

To put it simply, we recognise that western psychology and traditional psychotherapy was designed around the needs of a very specific group of people, so we need to take active steps if we want our work as therapists to be sensible, meaningful, and usable to people outside of that group. You don’t have to go back very far for all research and writing to be about and by white, Anglo-Saxon, middle-class, able-bodied, straight (or straight passing), cisgender (or cis passing) people. Of these, those with the biggest voices and who had the most power to define what was ‘healthy’ and ‘normal’ were men. As a result, most people in the world don’t fit these descriptions and can easily be blamed or stigmatised because they need something different from their therapy or their life. Being Accessible comes down to understanding this and choosing a different way of working, in which we aim to value, understand, and meet the needs of everyone, no matter what these look like.

Who do we need to consider?

The short answer? Everyone! Even a client who fits into all of the boxes listed above might need some flexibility. The very basic core to having an accessible practice is that you work with your client’s individual needs instead of trying to get them to fit into the way you think you should be working, what you think therapy should look like, or what you think they should need.

So are you saying my needs don’t matter?

Absolutely not! You are (and must be) part of the ‘as many people as possible’ mentioned earlier. If you have to set a specific price in order to sustain yourself, or you can’t work certain times, or you practice in an area someone doesn’t feel safe in, that doesn’t mean you are doing accessibility wrong. It just means your service is not the right one for that person – you will never be Accessible to everyone. That doesn’t make you wrong, and it’s important to remember that it doesn’t make them wrong, either.

We are not suggesting that you must sacrifice everything to meet everyone’s needs – we are challenging you to really reflect, in each case individually, on what you can do. And this goes both ways – saying ‘yes’ to every client because you expect your work to be right for everyone is just as inaccessible as saying ‘no’ to anyone who asks for flexibility or something different from your usual.

By law, you can’t discriminate against someone because of age, disability (including a mental health condition), gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy or parenthood, race (including ethnicity or nationality), religion or belief, sex (not explicitly including gender identity and intersexuality), and sexual orientation. This means you can’t give someone a lesser service or refuse to work with them because of these things. That being said, it is also important to be honest and self-aware about our limitations. If you don’t have the skills or capacity to work with someone’s main issues, it is generally accepted that you shouldn’t take them on as a client – the same goes for if you know you would have trouble working with someone because of a legally protected characteristic. It’s important to understand the difference between recognising your limits and having discriminatory biases. For example:

- Someone who believes autistic people can’t engage in therapy would be discriminatory, whereas someone who recognises they don’t know enough about autism would be acting ethically by not taking on an autistic client. That being said, they should consider accessing training, advice, or supervision on the topic to improve their work and awareness.

- Someone who has recently experienced a miscarriage should consider whether to take on a new, pregnant client, but it would be discriminatory to refuse this client because of an assumption that they won’t be as reliable because of their pregnancy.

Ethical guidelines and an accessible attitude require us to go beyond legal requirements. There are many characteristics, backgrounds, and identities that might be discriminated against or have different needs from the so-called ‘norm’. We should not feel justified to hold biases and prejudices about these just because they aren’t listed in a law written over a decade ago. We’ve started putting together a list of these, but we expect there are some we haven’t thought of yet (so please share your thoughts!):

- Economic status and background

- Educational background and ability

- Immigration status and background

- Criminal status and background

- Visible differences (both chosen and not – this can include markings, deformations, size, body modifications, attractiveness, style, etc)

- Lifestyle (relationship style/s, substance use, care responsibilities, diet, etc)

- Intersexuality (when someone’s physical sex characteristics like chromosomes or genitals do not fit the male/female binary) and non-binary identity (when someone’s gender identity does not fit the male/female binary)

- Social status and background

- Language abilities

- Living conditions (detainment, sheltered accommodation, homelessness, etc)

A thought on binaries and adjustments

There is a strict definition about who has a legal right to flexibility and who doesn’t. It seems to imply that people either need it 0% or 100%. We understand this is necessary in the law, but we also want to challenge you to question it within your own practice. If you can, for example, offer flexible timings to someone who is disabled, why not have that as an option for all your clients? Do you feel they deserve or need it less?

Note: We have not named class specifically within our additional list because we recognise that this is a nuanced combination of a number of these different elements, often changing from person to person. It should go without saying, though, that we recognise that classism is one of the most entrenched and accepted forms of prejudice and discrimination in the UK and that we are committed to fighting it within the mental health field.

How do I become Accessible?

On the ‘why’ of boundaries

Traditional attitudes to boundaries were that they had to be in place to protect the therapist from a client who wanted power over them. We reject this idea (we love giving power to clients!), but we still deeply value boundaries.

Prentis Hemphill defines boundaries as “the distance at which I can love you and me simultaneously”. We encourage practitioners to set boundaries that allow them to do their best work, rather than based on assumptions that they are in a battle with their clients.

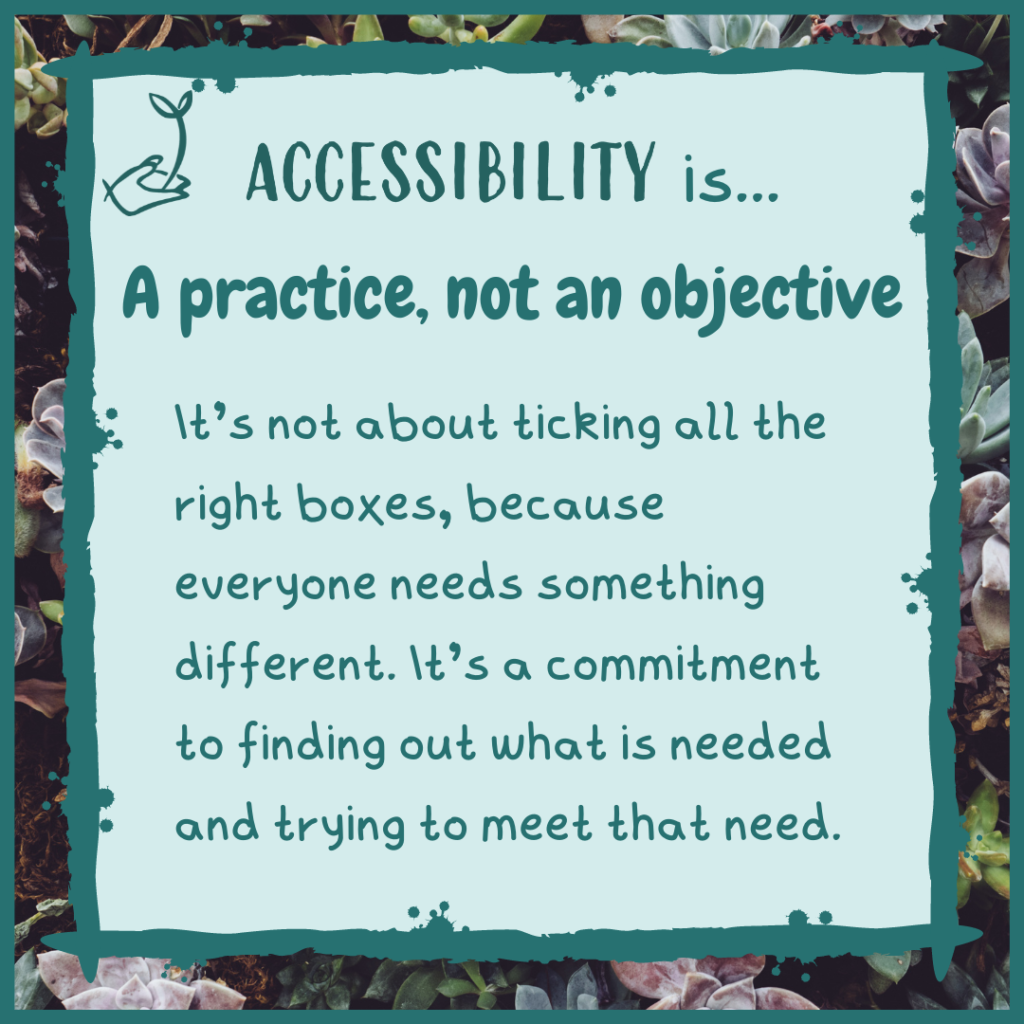

There’s good and bad news on this. On the one hand, you’re never going to achieve the status of Accessible, because it’s not something you can reach and be done with. On the other hand, it means that you don’t have to worry about a long list of changes you need to make to the way you work before you can think of yourself as an Accessible therapist. The key to it is building a habit, skillset, and commitment to trying to meet your clients’ needs as best you can.

Different people need different things. The client who cares for their elderly mother and the one who has a busy job might find it more Accessible to be able to book in a therapy session at a different time each week. The client who finds it hard to commit to their well-being or feels safer within a structured schedule, on the other hand, will find it more Accessible to have regular sessions at the same day and time each week or fortnight.

And then there’s you – maybe you need a set schedule because you have too many clients to ethically offer flexibility, or maybe you can’t guarantee the same time each week because you travel a lot for another job. And remember, what you need doesn’t have to be because of practical reasons, it might be that you would get too anxious with an ever-changing schedule, which would negatively affect your clients as well as yourself.

So Accessible doesn’t mean you say ‘Yes’ to every request, or pressure yourself to be flexible in all ways. Accessible means that your focus is on valuing and understanding, rather than judging or rejecting, your client’s individual needs. It means really checking in with yourself when your reaction is ‘I don’t/can’t offer that’, and making sure that it comes from your genuine need, rather than from assumptions, defensiveness, or social/professional expectations. It means not imposing limited definitions of ‘healthy’, ‘correct’, or ‘good’ on your clients OR on your way of working.

What could adjustments and flexibility look like? Here’s a few examples:

- Having shorter or longer sessions so the client isn’t overwhelmed or rushed

- Doing the therapy session in an unconventional place that feels safer to the client

- Offering additional support, like attending a meeting or speaking outside of specific session times

- Working within the client’s spiritual practices even if they are different from yours

- Exploring different forms of communication like writing, drawing, movement, and translators

- Allowing another person in the room, whether for an individual session or on an ongoing basis

Always make sure to explore options with appropriate supervision and within ethical frameworks. The aim of being Accessible is never an excuse to act unethically, dangerously, or without reflection.

The importance of awareness

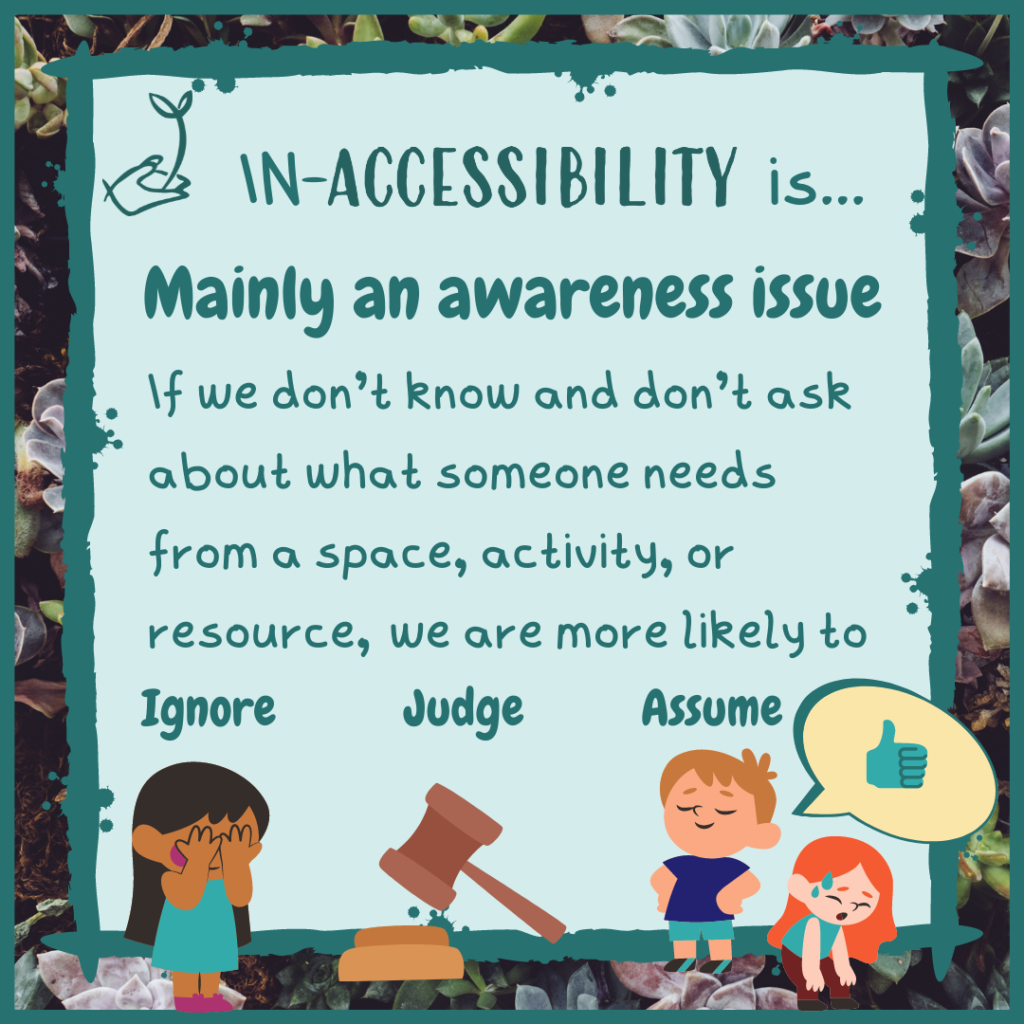

Being Accessible isn’t just about considering adjustments that are requested by clients – sometimes a client won’t know what to ask for or is afraid to ask. As the people providing the service, it is our responsibility to be be mindful and aware of how therapy is impacting someone. Context and knowledge can be a huge help with this.

Most of the time, a service or space won’t be Accessible because it’s based on the assumption that everyone needs the same things. This can result in a client’s needs being missed even when they are visible or communicated. There is a common phrase about this – “a square peg in a round hole”. If we don’t know that square pegs exist, or that they need square holes, we might judge or blame the square peg for not fitting. Even worse, we might think it fits just fine and move on, leaving it to suffer on its own!

Like we mentioned above, most of our ideas about what is ‘healthy’ and ‘normal’, and about what therapy should look like, is based on a very specific group of people and the opinions of an even more limited group. This means that to be Accessible we need to put an active effort into becoming more open and knowledgeable to the other possibilities of person, need, and goal that are out there.

Have a look at our lists above of different characteristics, identities, and backgrounds

- What are your assumptions about the people who you are similar to and what they need? If a client has a similar background to you, you might expect them to want the same support you found helpful.

_____________________________________________ - What do you know about the elements of these lists that are different from you? If you’ve had training or done some reading about something, was this by someone with personal experience, or by an ‘expert’ who is talking about an ‘other’ and what they need? If you haven’t accessed any training or reading about it, why not?

_____________________________________________ - What is your personal experience of people who are different from you in these ways? If you’ve only ever interacted with a certain group when providing support, it might be harder to have a view of them as healthy, independent, and knowledgeable. You can try changing up that experience by interacting socially, through online groups, or through novels and stories by authors from that group.

Keep in mind that most assumptions and biases, by nature, are outside of our awareness. This means you don’t have to beat yourself up for having them AND that you might not feel like these tips are necessary for you. Many therapists like to think that they don’t need to know about a specific group because they treat everyone with the same level of empathy, but this is not reflected in client experiences. Challenge yourself to be open to the possibility that, like everyone else, you can’t be neutral and are impacted by what you’re exposed to.

Our Accessibility tips